Not all dementia is the same

When someone says "dementia," most people think of memory loss-forgetting names, missing appointments, repeating questions. But that’s only part of the story. Vascular dementia, frontotemporal dementia (FTD), and Lewy body dementia (LBD) are three very different conditions that all fall under the dementia umbrella. They affect different parts of the brain, show up in different ways, and need completely different approaches to care. Misdiagnosing one for another can lead to dangerous side effects, especially with medications. Understanding the differences isn’t just helpful-it can be life-saving.

Vascular dementia: Damage from blocked blood flow

Vascular dementia happens when blood flow to the brain gets cut off, usually because of strokes or long-term damage to blood vessels. High blood pressure, diabetes, and high cholesterol are the usual suspects. It’s the second most common type of dementia after Alzheimer’s, making up about 10% of cases worldwide.

Unlike Alzheimer’s, which fades slowly, vascular dementia often steps down in stages. A person might seem fine for months, then suddenly get worse after a mini-stroke (TIA) or a full stroke. After that, they might stabilize again-until the next event. This stepwise decline is a key clue doctors look for.

Symptoms include trouble planning, following instructions, or remembering recent events. People may also struggle with movement-stiffness, balance issues, or walking slowly. Hallucinations and delusions can show up too, but they’re less common than in Lewy body dementia.

There’s no cure, but managing the root cause can slow things down. Keeping blood pressure under 130/80 mmHg, controlling blood sugar, and taking low-dose aspirin if recommended can reduce future brain damage. Brain scans like MRI are critical for diagnosis-they show the areas where blood flow was lost. The good news? Preventing vascular dementia is often possible. Controlling those risk factors cuts dementia risk by up to 20%.

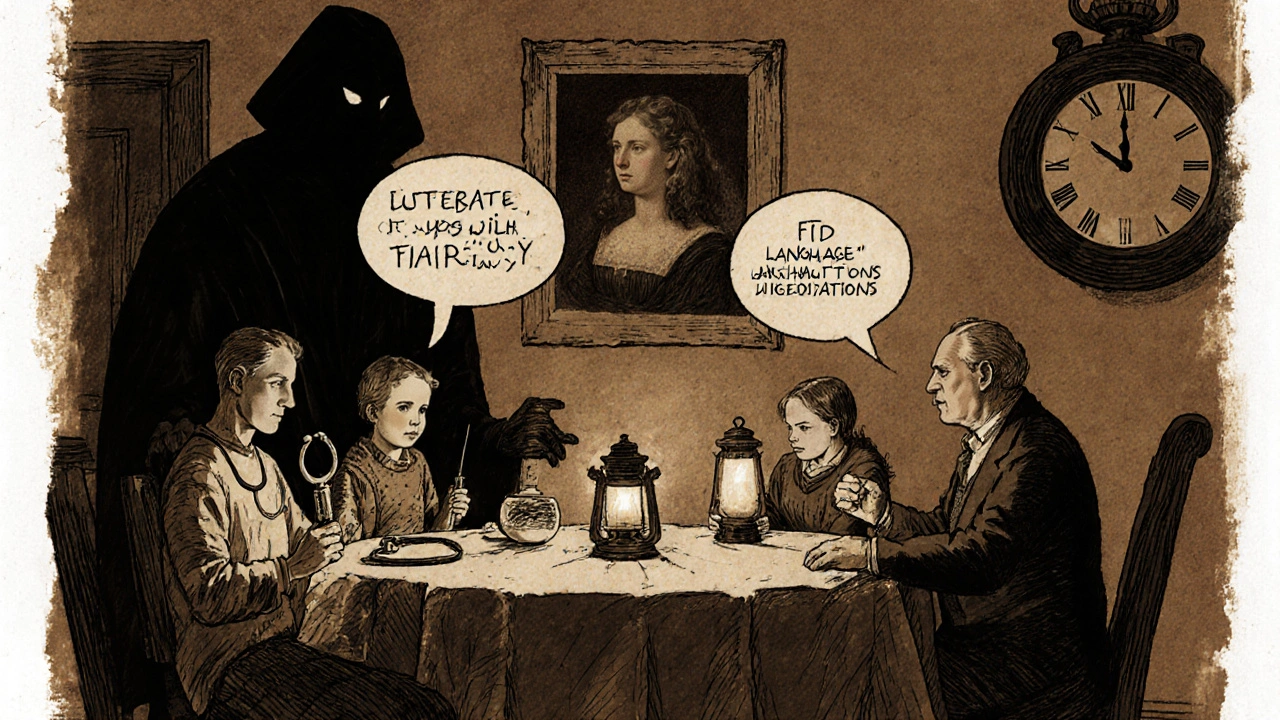

Frontotemporal dementia: Personality changes before memory loss

Frontotemporal dementia doesn’t usually start with forgetfulness. It starts with behavior. Someone who was polite and organized suddenly makes inappropriate comments, spends money recklessly, or loses all interest in family. They might stop caring about hygiene, eat compulsively, or become emotionally flat. This is FTD-and it often hits people in their 50s or early 60s, making it the most common dementia in people under 60.

It’s named for the brain areas it damages: the frontal and temporal lobes. These are the regions that control judgment, social behavior, language, and emotional control. The brain tissue shrinks because of abnormal proteins-tau or TDP-43-that build up and kill nerve cells.

Memory stays surprisingly intact in the early stages. Someone might remember your name but not know how to act around you. That’s why FTD is often mistaken for depression, bipolar disorder, or even schizophrenia. Up to half of all cases are misdiagnosed as psychiatric problems at first.

There are three main types: behavioral variant (personality changes), primary progressive aphasia (language trouble), and movement disorders (similar to Parkinson’s). Diagnosis relies on MRI scans showing shrinkage in the front and sides of the brain, plus neuropsychological tests that check for executive function, not memory.

Medications don’t stop the disease, but SSRIs can help with compulsive behaviors or mood swings. Speech therapy helps those with language loss. The hardest part? It strikes people in their prime-while they’re still working, raising kids, or caring for aging parents. Families need support, not just medical care.

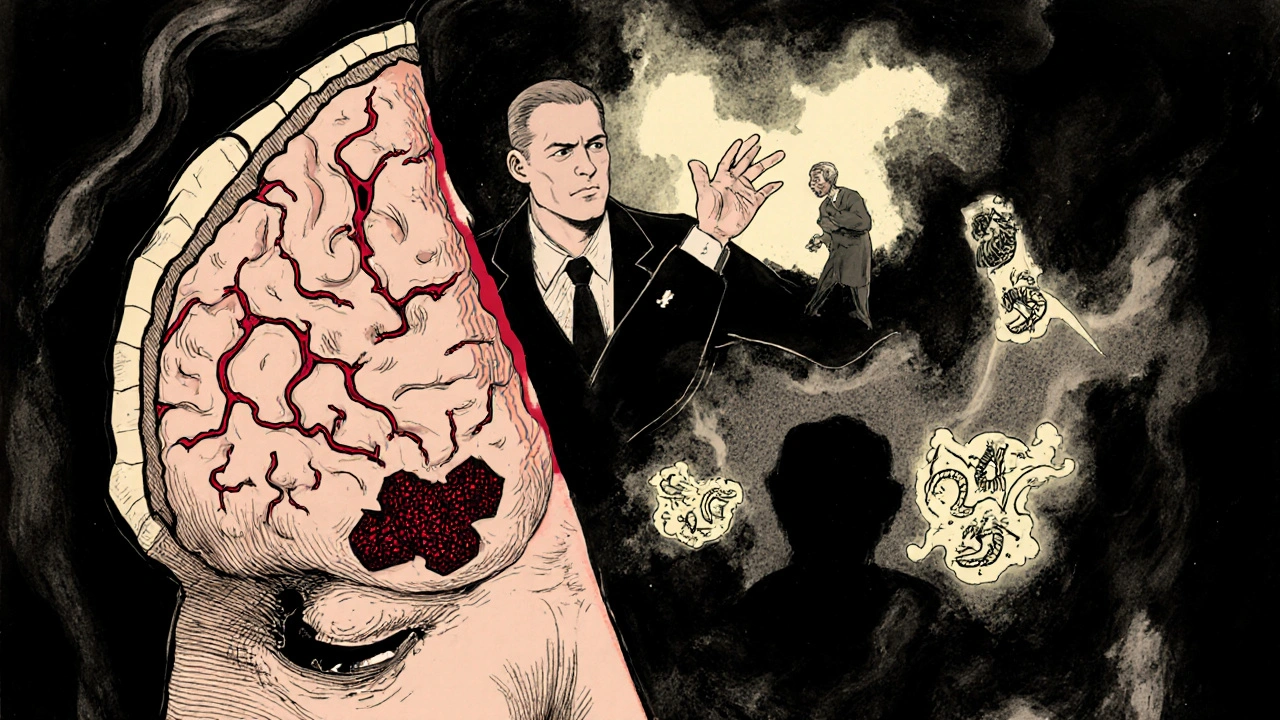

Lewy body dementia: Hallucinations, fluctuations, and movement issues

Lewy body dementia is the third most common type, affecting about 1.4 million people in the U.S. alone. It’s caused by clumps of a protein called alpha-synuclein-called Lewy bodies-that build up in brain regions that control thinking, movement, and sleep.

What makes it stand out? Three things: fluctuating alertness, visual hallucinations, and Parkinson-like movement symptoms. One day, a person might be sharp and alert. The next, they’re confused, staring into space, barely responding. Hallucinations aren’t rare-they’re common. People see people, animals, or shadows that aren’t there. Unlike in Alzheimer’s, they often don’t realize these aren’t real.

Another big clue: REM sleep behavior disorder. People act out their dreams-kicking, yelling, even jumping out of bed. This often shows up years before dementia starts.

Movement symptoms include stiffness, slow motion, shuffling steps, and reduced facial expression. But here’s the catch: memory loss isn’t the first sign. People might forget where they put their keys, but they don’t forget their grandchildren’s names-at least not yet.

Diagnosis is tricky. Doctors look for at least two of the four core symptoms: fluctuations, hallucinations, REM sleep disorder, and Parkinsonism. DaTscan imaging can help by showing reduced dopamine activity in the brain.

Medications are a minefield. Drugs used for Alzheimer’s-like donepezil or rivastigmine-can help with thinking and behavior. But typical antipsychotics? Dangerous. Up to 75% of people with LBD have severe, even life-threatening reactions. Sedation, extreme stiffness, or neuroleptic malignant syndrome can happen. Even mild antipsychotics need extreme caution.

How they compare: Side by side

| Feature | Vascular Dementia | Frontotemporal Dementia (FTD) | Lewy Body Dementia (LBD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary cause | Blocked or damaged blood vessels | Build-up of tau or TDP-43 proteins in frontal/temporal lobes | Alpha-synuclein deposits (Lewy bodies) in brainstem and cortex |

| Typical age of onset | 65+ | 45-65 (often younger than other dementias) | 50+ |

| Memory loss early on? | Yes, but not always first | No-often preserved until late stages | No-less prominent than behavior or movement issues |

| Key symptoms | Stepwise decline, trouble planning, movement problems | Personality changes, social inappropriateness, language trouble | Fluctuating attention, visual hallucinations, Parkinsonism, REM sleep disorder |

| Diagnostic tool | Brain MRI showing infarcts or white matter damage | MRI showing frontal/temporal atrophy; FDG-PET | McKeith criteria + DaTscan for dopamine loss |

| Key treatment focus | Control blood pressure, diabetes, cholesterol | SSRIs for behavior; speech therapy | Cholinesterase inhibitors; avoid antipsychotics |

| Prognosis | Varies with vascular events; can stabilize between strokes | Progresses steadily; survival 6-10 years | 5-8 years after diagnosis |

Why getting the diagnosis right matters

Imagine someone with Lewy body dementia is given an antipsychotic because they’re seeing things. They might go from being able to walk to being completely rigid, unable to move. That’s not rare-it’s well-documented. About 50-75% of LBD patients react badly to these drugs. The same goes for FTD: if a doctor thinks it’s depression, they’ll prescribe antidepressants, but the real problem is brain damage-not mood.

And vascular dementia? If you don’t treat high blood pressure, the next stroke could be the one that takes away speech or mobility. Every untreated risk factor is a ticking clock.

Accurate diagnosis means the right care plan. For LBD, that means avoiding certain meds and using cholinesterase inhibitors. For FTD, it means behavioral strategies and therapy instead of antidepressants. For vascular dementia, it’s about heart health.

Even with all the tools we have, misdiagnosis is still common. LBD is mistaken for Alzheimer’s in up to 75% of initial cases. FTD gets labeled as psychiatric illness. Vascular dementia is often written off as "just aging." That’s why seeing a neurologist who specializes in dementia is so important.

What’s next: Research and hope

While there’s still no cure, research is moving faster than ever. Blood tests are now being developed to detect early signs of brain damage-like GFAP for vascular injury or alpha-synuclein for LBD. In LBD, drugs like prasinezumab are being tested to clear Lewy bodies. For FTD, gene-targeting therapies are in trials for people with inherited forms.

The SPRINT-MIND trial showed that lowering systolic blood pressure to under 120 mmHg reduced mild cognitive impairment by 19%. That’s a big win for vascular dementia prevention.

But funding doesn’t match need. Alzheimer’s gets billions in research money. LBD and FTD together get less than $50 million annually-even though they affect millions. That’s changing slowly, but awareness is the first step.

What families should know

If you’re caring for someone with one of these dementias, education is your best tool. For LBD, learn that hallucinations aren’t always scary to the person-they might be talking to a long-dead relative and think it’s normal. Don’t argue. Just redirect.

For FTD, understand that the person isn’t being rude-they’ve lost the ability to filter thoughts. It’s not defiance. It’s brain damage.

For vascular dementia, every doctor’s visit is a chance to check blood pressure, cholesterol, and blood sugar. Small changes add up.

And don’t wait for a crisis. If someone’s behavior changes suddenly, or they start seeing things, or their movement slows-get them evaluated. Early diagnosis means better outcomes, fewer hospital visits, and more time with dignity.

Can vascular dementia be reversed?

No, brain damage from strokes or blocked vessels can’t be undone. But further damage can be prevented. Controlling blood pressure, cholesterol, and blood sugar stops new strokes and slows cognitive decline. Many people stabilize after the first few events if risk factors are managed well.

Is frontotemporal dementia inherited?

About 10-30% of FTD cases have a strong family history, often linked to mutations in genes like C9orf72, MAPT, or GRN. If multiple family members have FTD, dementia, or ALS, genetic counseling is recommended. But most cases are not inherited.

Why do people with Lewy body dementia have hallucinations?

Lewy bodies build up in brain areas that process visual information and regulate perception. This disrupts how the brain interprets what the eyes see, leading to false images. These aren’t delusions-they’re true hallucinations caused by brain changes. People often don’t realize they’re not real, so arguing with them doesn’t help.

Can you have more than one type of dementia?

Yes. Mixed dementia is common-especially Alzheimer’s plus vascular dementia. About 40% of Alzheimer’s patients also have Lewy bodies. This makes diagnosis harder and symptoms more complex. Treatment must address all contributing factors.

What’s the best way to get a correct diagnosis?

See a neurologist who specializes in dementia. They’ll use brain imaging (MRI, PET scans), detailed cognitive testing, and a full medical history. For LBD, they’ll ask about sleep behaviors and movement. For FTD, they’ll assess personality and language changes. Don’t rely on a general practitioner alone-specialists catch the subtle signs.

Final thoughts

Dementia isn’t one disease. It’s a group of conditions with different causes, symptoms, and treatments. Vascular dementia is about blood flow. Frontotemporal dementia is about personality and language. Lewy body dementia is about fluctuating minds and movement. Understanding the difference isn’t academic-it’s practical. It changes how you talk to your loved one, how you respond to their behavior, and what medications are safe. Getting it right means better care, fewer emergencies, and more time together.

Write a comment