Asthma Risk Calculator

Enter your current environmental conditions to assess your asthma risk level based on climate change impacts.

Ever wonder why asthma attacks seem to be popping up more often during heat waves or smoggy days? The answer lies in a growing link between the planet’s shifting climate and a condition many of us know all too well: bronchial asthma. In the next few minutes you’ll see how rising temps, wild weather, and worsening air quality are turning the lungs of millions into a more fragile landscape.

What is bronchial asthma?

Bronchial Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disease of the airways that causes wheezing, shortness of breath, chest tightness, and coughing. It affects around 339million people worldwide, according to the World Health Organization, and it doesn’t discriminate - kids, adults, and seniors can all experience flare‑ups.

Climate change: the big picture

Climate Change refers to long‑term shifts in temperature, precipitation, and wind patterns driven primarily by human‑generated greenhouse‑gas emissions. While the headlines often focus on sea‑level rise or extreme storms, the subtle, day‑to‑day changes in the air we breathe are equally important for asthma sufferers.

Hotter days, tighter airways

As global average temperatures climb, heat waves become more frequent and intense. Hot, humid air can irritate the Respiratory System, making the bronchial tubes swell faster. Research from the European Respiratory Journal showed that each 1°C rise in temperature can increase emergency asthma visits by up to 2%.

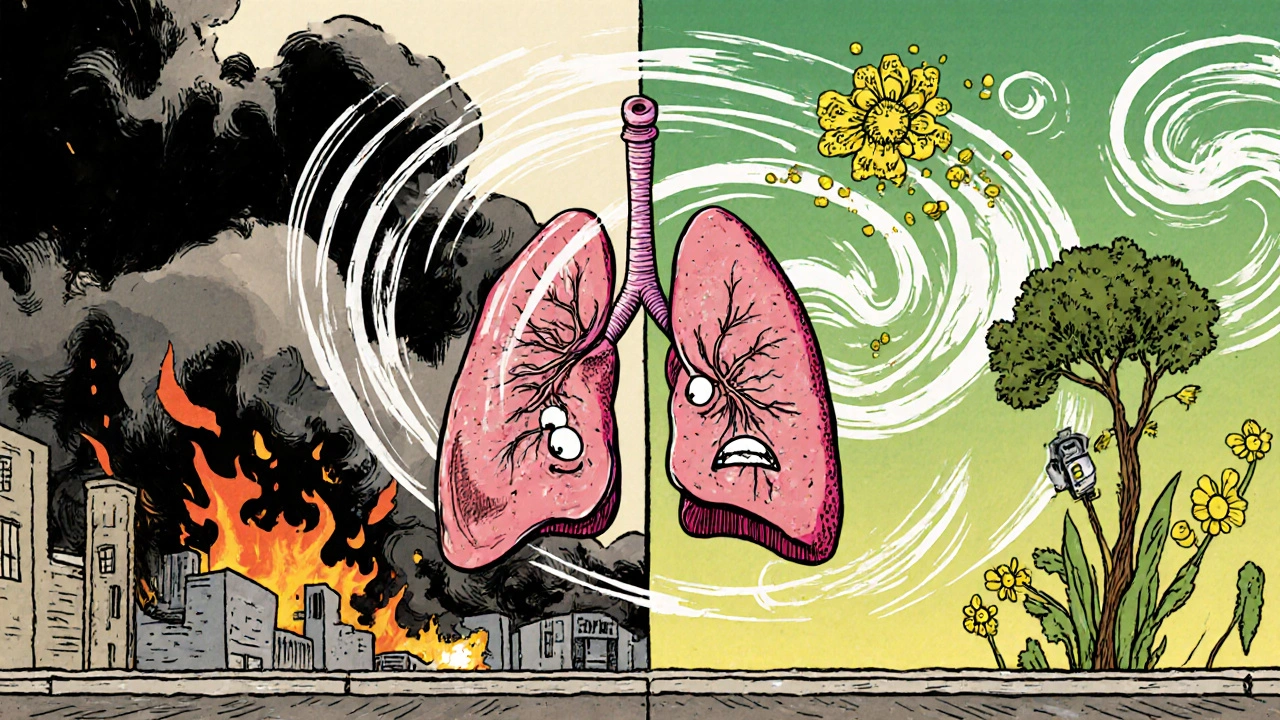

Air pollution: the silent partner

Climate change and air pollution are intertwined. Higher temperatures boost the formation of ground‑level ozone, a powerful respiratory irritant. At the same time, wildfires driven by drought release massive clouds of Particulate Matter (PM2.5), tiny particles that slip deep into the lungs. Both ozone and PM2.5 are classified by the EPA as major triggers for asthma attacks.

Allergy season is stretching out

Warmer springs and longer growing seasons mean plants produce pollen for more weeks each year. Pollen counts have risen by 20% in many temperate regions over the past two decades. For a person with bronchial asthma, that extra pollen is another nail in the coffin of airway stability.

Who feels the heat most?

Children’s airways are smaller, so pollutants and allergens can cause proportionally larger blockages. Seniors often have reduced lung capacity, making it harder to recover from a severe flare‑up. Socio‑economic factors matter too - communities near highways or industrial zones tend to experience higher pollutant loads.

What the research says

Multiple studies paint a clear picture:

- A 2023 CDC analysis linked days with Ozone levels above 70ppb to a 15% spike in asthma‑related ER visits.

- Data from the Global Burden of Disease project estimate that by 2030, climate‑related air pollution could add 2‑3million new asthma cases worldwide.

- Longitudinal studies in Australia found that children exposed to more than 10µg/m³ of PM2.5 during their first five years had a 12% higher risk of developing chronic asthma.

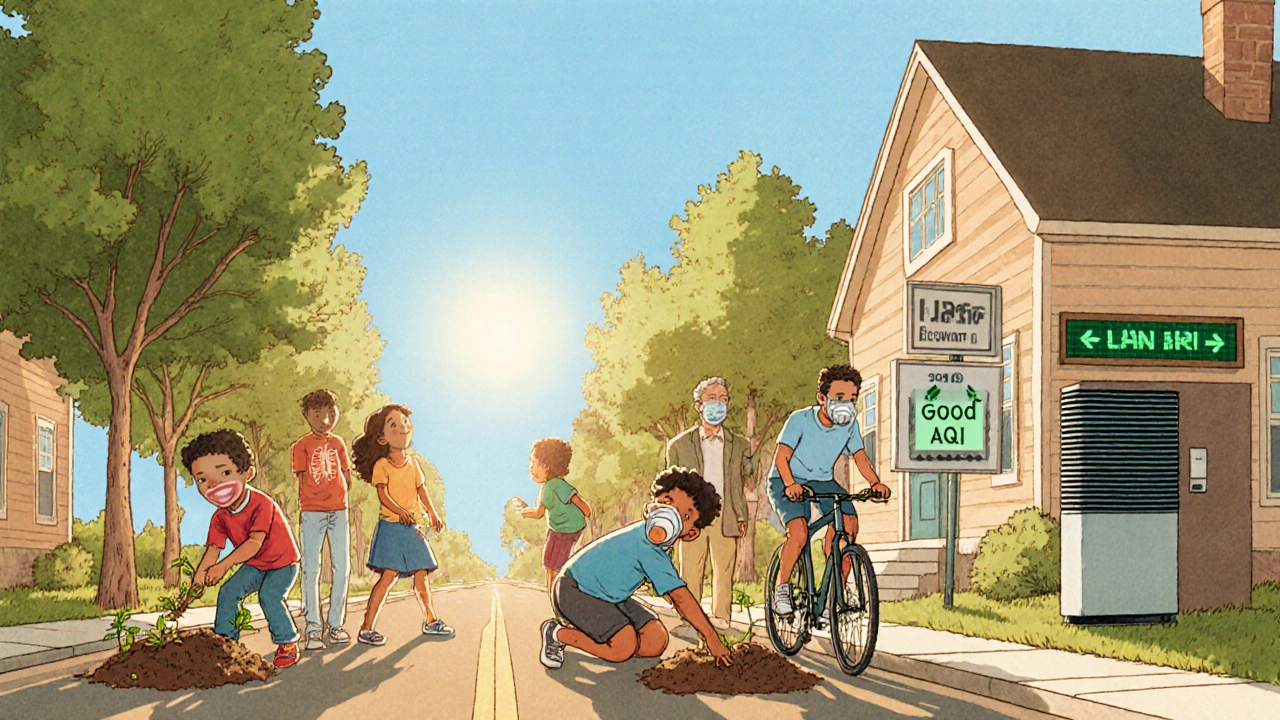

How to protect yourself

While we wait for policy changes, there are practical steps you can take right now:

- Check daily air‑quality indexes (AQI) on your phone. If the AQI is ‘unhealthy for sensitive groups’, stay indoors.

- Use a HEPA air purifier in bedrooms and living areas. Studies show HEPA filters can cut indoor PM2.5 by up to 60%.

- Keep windows closed during high‑pollen days. Many weather apps now include pollen forecasts.

- Stay hydrated - thin mucus and make it easier to clear irritants.

- Talk to your doctor about adjusting inhaler doses during peak‑pollution seasons.

Policy and public‑health actions

Long‑term solutions require coordinated action:

- Stronger emissions standards for vehicles and power plants to curb ozone precursors.

- Urban‑tree planting programs that absorb pollutants and provide shade, reducing heat‑island effects.

- Investment in early‑warning systems that alert vulnerable communities before wildfire smoke spreads.

- School‑based asthma education that teaches children how to recognize and respond to triggers.

What the future may hold

Climate models predict that by 2050, average global temperatures could be 1.5°C higher than pre‑industrial levels. If emissions aren’t curbed, we could see:

- Annual increase of 10‑15% in ozone‑related asthma emergencies.

- Longer allergy seasons extending up to three additional months.

- Higher baseline rates of chronic bronchial inflammation in urban populations.

Understanding these trends helps doctors, patients, and policymakers prepare better strategies.

Key takeaways

- Heat, ozone, and particulate matter are the three climate‑driven factors that most aggravate bronchial asthma.

- Longer pollen seasons add a seasonal layer of risk, especially for children.

- Monitoring air quality, using HEPA filters, and adjusting medication can reduce flare‑ups.

- Community‑level actions-cleaner energy, more green space, early‑warning alerts-are essential for long‑term health.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can hot weather alone trigger an asthma attack?

Yes. High temperatures increase airway inflammation and can amplify the effects of pollutants already in the air, making attacks more likely.

Is there a link between wildfire smoke and asthma?

Wildfire smoke contains high levels of PM2.5 and toxic gases. Exposure can cause immediate bronchoconstriction and long‑term lung function decline, especially in asthma patients.

How often should I check the air‑quality index?

At least once a day, and more often if you notice symptoms. Many apps provide real‑time alerts when AQI reaches ‘unhealthy’ levels.

Do indoor plants help reduce asthma triggers?

Some plants can lower indoor CO₂ and humidity, but they can also release pollen or mold spores. Choose low‑allergen varieties like snake plant and keep soil dry.

Should I change my medication during high‑pollution days?

Talk to your healthcare provider. Many doctors recommend a short‑acting bronchodilator before outdoor activities when AQI is poor.

Comparison of Climate Factors and Their Asthma Impact

| Factor | Typical Climate Change Shift | Direct Effect on Asthma | Common Mitigation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | +1-2°C average by 2030 | Increased airway inflammation; higher bronchodilator use | Stay indoors during heat spikes; hydrate; use fans with filters |

| Ozone | Seasonal peaks rise 10‑15ppb | Irritates bronchial lining; triggers cough | Check AQI; limit outdoor exertion when ozone >70ppb |

| Particulate Matter (PM2.5) | Frequent wildfire events, higher baseline levels | Deep‑lung penetration; chronic inflammation | Use HEPA purifiers; wear N95 masks during smoke events |

| Pollen | Season extended by 2-3 weeks | Allergic sensitization; increased wheeze | Monitor pollen forecasts; keep windows closed; shower after outdoors |

Write a comment