Pancreatitis Risk Assessment Tool

Pancreatitis Risk Assessment

This tool helps you understand your risk of developing pancreatitis based on key factors. Remember that this is for informational purposes only and should not replace professional medical advice.

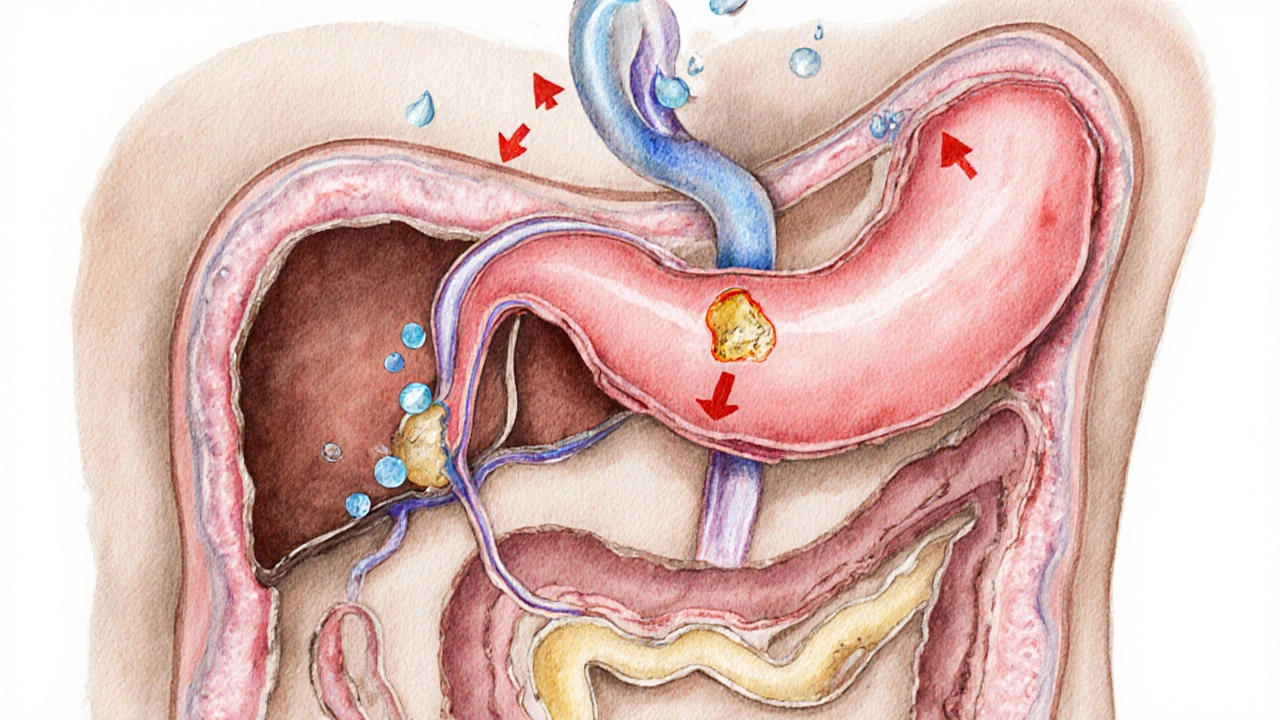

Feeling a sharp or burning ache right under the breastbone can be alarming. That area, known as the epigastrium, houses the stomach, duodenum, and the pancreas. When pain there is linked to inflammation of the pancreas, the condition is called Pancreatitis. This guide breaks down what triggers the pain, how to spot the warning signs, and which steps can calm the inflammation before it turns serious.

Key Takeaways

- Epigastric pain often signals pancreatic irritation, especially when accompanied by nausea, vomiting, or elevated enzymes.

- Two main forms exist: acute pancreatitis (sudden onset) and chronic pancreatitis (repeating damage).

- Gallstones and excessive alcohol are the top causes, but high triglycerides, certain meds, and infections also play a role.

- Diagnosis relies on blood tests (serum lipase, amylase), imaging (CT, MRI, ultrasound), and sometimes endoscopic procedures.

- Treatment ranges from hospital‑based fasting and IV fluids to long‑term diet changes, enzyme supplements, and lifestyle adjustments.

What Does Epigastric Pain Mean?

The term Epigastric Pain describes discomfort centered in the upper middle abdomen, just below the breastbone. It can feel like a dull ache, a sharp stab, or a burning sensation. Common culprits include heartburn, gastritis, ulcers, and the pancreas.

When the pain intensifies after eating, radiates to the back, or is paired with fever, it often points to pancreatic involvement. Unlike heart‑related chest pain, epigastric pain usually worsens when you lie flat and eases when you lean forward.

Pancreatitis Explained

Pancreatitis is the inflammation of the pancreas, an organ tucked behind the stomach that releases digestive enzymes and hormones like insulin. The inflammation can be sudden (acute) or develop over years (chronic). In both cases, the pancreas’s own enzymes start attacking its tissue, causing pain and swelling.

The pancreas itself is a Pancreas, a gland about 6 inches long that sits across the back of the abdomen. Its exocrine part produces enzymes (lipase, amylase) that break down fats, carbs, and proteins, while the endocrine part manages blood‑sugar levels through insulin and glucagon.

Top Triggers of Pancreatitis

- Gallstones: Small stones that form in the gallbladder can block the pancreatic duct, forcing enzymes to back up.

- Alcohol Abuse: Heavy, chronic drinking irritates pancreatic cells and raises toxic metabolite levels.

- High triglyceride levels (above 1,000mg/dL) that overload the pancreas.

- Certain medications (e.g., corticosteroids, some HIV drugs, azathioprine).

- Autoimmune attacks, genetic mutations (PRSS1, SPINK1), and infections (mumps, coxsackievirus).

Most patients have at least one of the first two triggers, but a combination or an obscure cause is not uncommon.

Symptoms: Acute vs. Chronic

Both forms share core signs, yet they differ in timing, severity, and accompanying features.

| Aspect | Acute Pancreatitis | Chronic Pancreatitis |

|---|---|---|

| Onset | Sudden, often hours | Gradual, weeks to months |

| Pain pattern | Severe epigastric pain radiating to the back, worsens after meals | Persistent dull ache, may improve after fasting |

| Enzyme levels | Serum lipase/amylase >3× normal | Often normal or mildly elevated |

| Imaging | Enlarged pancreas, fluid collections on CT | Calcifications, ductal irregularities, atrophy |

| Complications | Necrotizing pancreatitis, organ failure | Pseudocysts, diabetes, malabsorption |

Regardless of type, the hallmark is pain centered in the epigastrium that often radiates toward the back. Nausea, vomiting, and a feeling of fullness are common companions.

How Doctors Diagnose Pancreatitis

Diagnosis is a stepwise process.

- Blood tests: The first clue comes from Serum Lipase and amylase. Lipase remains elevated longer, making it the preferred marker.

- Imaging: An Abdominal CT Scan is the gold standard for assessing severity and spotting necrosis. Ultrasound helps identify gallstones. MRI and MRCP (magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography) map the ducts without radiation.

- Endoscopic procedures: When gallstone blockage is suspected, an ERCP (endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography) can both diagnose and relieve the obstruction.

Doctors also review medical history (alcohol intake, medication list) and physical exam findings (tenderness, guarding) to piece together the picture.

Treatment Strategies

Therapy varies with the type and severity, but the core goals are the same: halt enzyme activation, support organ function, and prevent complications.

Acute Pancreatitis Management

- Hospital admission: Most patients need IV fluids (often 250‑500mL/hr) to maintain blood pressure and prevent shock.

- Fasting: The pancreas rests when you avoid food for 24‑48hours; nutrition is delivered intravenously or via a naso‑jejunal tube if prolonged.

- Pain control: Opioids (e.g., morphine) are common early on, switching to NSAIDs as pain lessens.

- Address cause: If gallstones are the culprit, a same‑day ERCP with stone removal or later cholecystectomy is recommended.

- Monitor complications: Regular labs and repeat imaging catch necrosis, infection, or organ failure early.

Chronic Pancreatitis Care

- Lifestyle overhaul: Complete abstinence from alcohol and a low‑fat diet (≤30g fat per day) reduce ongoing irritation.

- Enzyme supplementation: Pancreatic enzyme tablets taken with meals aid digestion and prevent malnutrition.

- Blood‑sugar management: Since chronic damage can impair insulin production, regular glucose monitoring and, if needed, insulin therapy are essential.

- Endoscopic or surgical options: For ductal blockages or strictures, stenting via ERCP or a Puestow lateral pancreaticojejunostomy may relieve pain.

- Nutritional support: A diet rich in lean protein, complex carbs, and vitamin‑rich fruits helps rebuild lost weight.

Dietary Guidelines for All Stages

Regardless of acute or chronic status, nutrition plays a starring role.

- Choose Low‑Fat Diet: Fat slows digestion and forces the pancreas to release more enzymes.

- Eat small, frequent meals: This prevents overstimulation of the pancreatic duct.

- Stay hydrated: Adequate fluids support blood flow to the pancreas.

- Avoid trigger foods: Fried items, high‑sugar desserts, and alcohol are top offenders.

Complications to Watch For

If left untreated, pancreatitis can spiral into serious problems.

- Pseudocyst: A fluid‑filled sac that can burst or become infected.

- Necrotizing pancreatitis: Death of pancreatic tissue may require surgical debridement.

- Diabetes mellitus: Loss of insulin‑producing cells leads to blood‑sugar issues.

- Malabsorption: Poor digestion of fat‑soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K) can cause deficiencies.

Prompt medical attention at the first sign of worsening pain, fever, or jaundice can curb these outcomes.

Preventing Future Episodes

Prevention hinges on tackling the root causes.

- Maintain a healthy weight: Obesity raises triglyceride levels, a known risk factor.

- Limit alcohol: Even moderate drinking can trigger flare‑ups in susceptible people.

- Control blood lipids: Statins or dietary omega‑3s keep triglycerides in check.

- Regular check‑ups: Early imaging for gallstones or ductal anomalies helps intervene before inflammation starts.

Quick Summary: When to Seek Help

If you experience sudden, severe epigastric pain that spreads to the back, especially with nausea, vomiting, or fever, treat it as a medical emergency. Call emergency services or head to the nearest hospital.

Frequently Asked Questions

What lab tests confirm pancreatitis?

Elevated serum lipase is the most reliable marker, typically three times the normal upper limit. Amylase may also rise, but it normalizes faster.

Can a gallstone blockage be treated without surgery?

Yes. Endoscopic removal via ERCP can clear the duct. However, most patients eventually need a cholecystectomy to prevent recurrence.

Is alcohol the only cause of chronic pancreatitis?

No. While alcohol is the leading cause, hereditary gene mutations, autoimmune disease, and long‑standing high triglycerides can also lead to chronic damage.

How long should I fast during an acute attack?

Typically 24‑48hours, until pain eases and lab values improve. Nutrition is then re‑introduced slowly, starting with clear liquids.

Can a low‑fat diet reverse chronic pancreatitis?

It can’t reverse scar tissue, but it reduces further inflammation, eases pain, and improves nutrient absorption when combined with enzyme replacement.

Write a comment