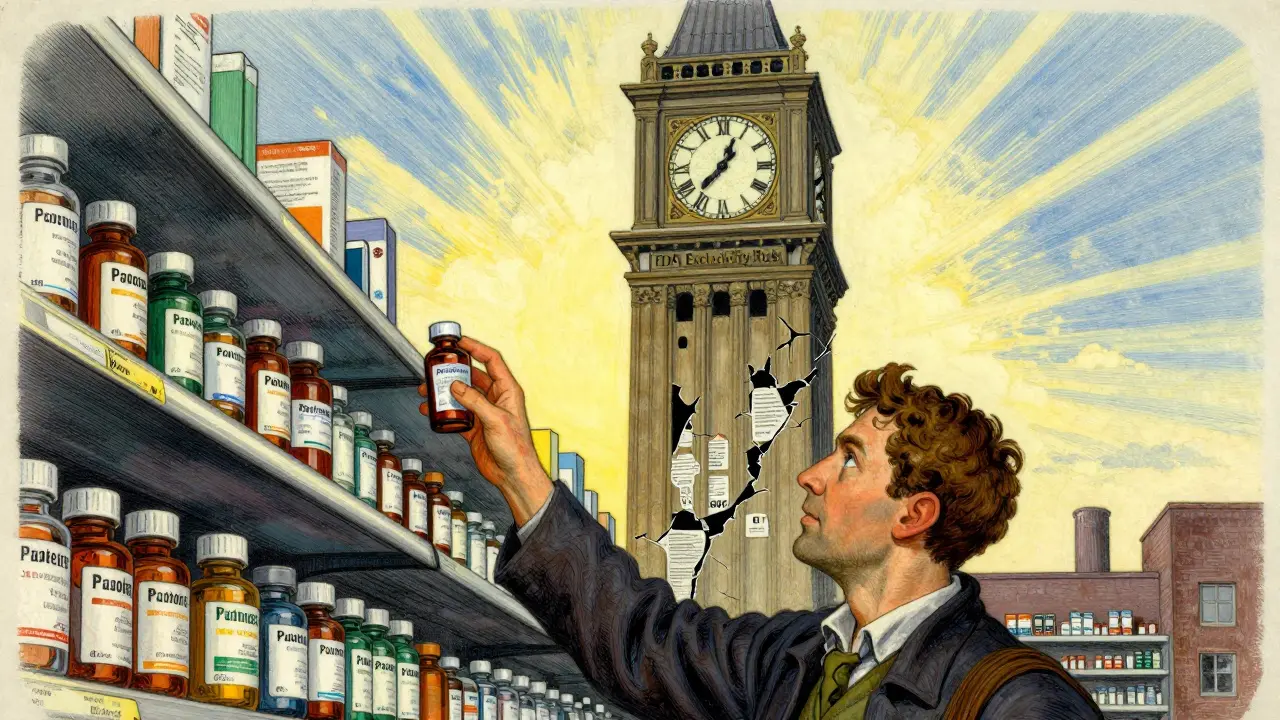

The U.S. generic drug market runs on a single, powerful rule: the first generic filer gets 180 days of exclusive rights to sell a generic version of a brand-name drug. No other company can enter during that time-not even if they’ve got the same drug, the same formula, and the same FDA approval. This isn’t a favor. It’s a legal incentive built into the system to shake up drug prices. And it works-sometimes.

How the 180-Day Clock Starts

This rule comes from the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984, a law designed to balance two things: protecting drug patents and letting generics in faster. The key is something called a Paragraph IV certification. When a generic company files an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA), they can challenge a patent on the brand drug by saying it’s invalid, unenforceable, or won’t be infringed. If they’re the first to do this, they lock in 180 days of exclusivity.

Here’s the twist: the clock doesn’t always start when the FDA approves the drug. It can start earlier. If a court rules in the generic company’s favor-saying the patent is invalid or not infringed-the exclusivity period begins right then, even if the FDA hasn’t given final approval yet. That means a company can win in court, sit on the approval, and block competitors for months or even years. The FDA can’t approve anyone else until that 180-day window runs out.

Why This Matters for Prices

Generic drugs make up 90% of prescriptions in the U.S. but cost only 22% of what brand drugs do. The first generic filer gets the lion’s share of those savings. During their 180 days, they typically capture 70-80% of the market. Some have made over a billion dollars in that window. Teva’s generic version of Copaxone, for example, brought in $1.2 billion in just six months.

This isn’t just about profit. It’s about access. Without this incentive, few companies would risk the cost and uncertainty of challenging a patent. Patent litigation can cost $5 million to $10 million. It takes 18-24 months of legal work, patent analysis, and regulatory prep. Only big players or well-funded startups can afford it. The 180-day exclusivity is the only thing that makes that gamble worth it.

The Dark Side: When the System Gets Stuck

But the system has a flaw. What if the first filer never launches? What if they win in court, get their exclusivity, then sit on it?

This happens more often than you think. Since 2010, about 45% of first filers either delayed their launch or never launched at all. Why? Sometimes, they strike a deal with the brand company. The brand pays them millions to hold off-what’s called a “reverse payment.” The FDA and FTC call this anti-competitive. A 2010 FTC study estimated these deals cost consumers $3.5 billion a year.

Another trick? The brand company launches its own generic version during the exclusivity period. It’s called an “authorized generic.” Same drug, same factory, same label-but it’s still the brand company selling it. The first filer gets nothing. The public gets a slightly cheaper drug, but not the full savings they were promised.

One infamous case involved insulin glargine. Sanofi fought the first generic filer in court and won, arguing the company delayed too long. That blocked other generics for 24 extra months. Patients waited two years longer than they should have for affordable insulin.

Who’s Winning and Who’s Losing

The big generic companies-Teva, Viatris, Sandoz-file over 65% of all Paragraph IV challenges. They have teams of lawyers, regulatory experts, and patent analysts. They’re built for this.

Smaller companies? Not so much. Only 15% of small generic firms use the FDA’s free assistance programs. Why? The rules are too complex. The paperwork is overwhelming. One regulatory consultant told a DIA forum: “You have to track filing times down to the second. Two companies can file the same day. Who wins? It’s a legal nightmare.”

And it’s not just about who files first. Sometimes, companies file on the same day to split the exclusivity. That’s a workaround. It’s legal. It’s messy. And it’s becoming more common.

What’s Changing Now

The FDA noticed the problem. In 2022, they proposed a fix: the 180-day clock should only start when the generic drug actually hits the market. Not when a court says so. Not when a patent is challenged. Only when the product is sold.

This would kill the “paper generic” loophole. No more sitting on approval. No more delaying competition. If you want exclusivity, you have to sell the drug.

Analysts say this change could speed up generic entry by 6-9 months for 40-50 drugs a year. That could save consumers $1.2 billion to $1.8 billion annually. The Congressional Budget Office estimates the current system costs Medicare $13 billion less in savings over ten years than a reformed version would.

But the brand drug industry is fighting back. PhRMA argues changing this would hurt innovation. If companies can’t count on exclusivity, they won’t challenge patents. Fewer generics. Higher prices. It’s a gamble.

What This Means for Patients

If you’re on a brand-name drug with a patent about to expire, here’s what to watch for:

- Is there a Paragraph IV certification filed? That’s your signal.

- Did the generic company win a court case? That’s when the clock starts-even if the drug isn’t on shelves yet.

- Is the brand company launching its own generic? That’s a red flag.

- Is it been over a year since the first filing? If so, the exclusivity may have been forfeited.

Patients don’t see the legal battles. They just see the price. And right now, the system is designed to make that price drop-but too often, it doesn’t.

What’s Next

The FDA’s proposed reform is still under review. Congress hasn’t acted. Meanwhile, the clock keeps ticking-sometimes on paper, sometimes on shelves.

One thing is clear: the 180-day exclusivity rule was meant to bring down drug prices. It did-for a while. But now, it’s being used as a tool to delay competition. The next chapter will decide whether it stays a lifeline for patients… or becomes another loophole for big pharma.

Write a comment